Burgess Memories: Ben Forkner

-

Ben Forkner

- 30th April 2025

-

category

- Blog Posts

Introduction to One Man’s Chorus by Ben Forkner

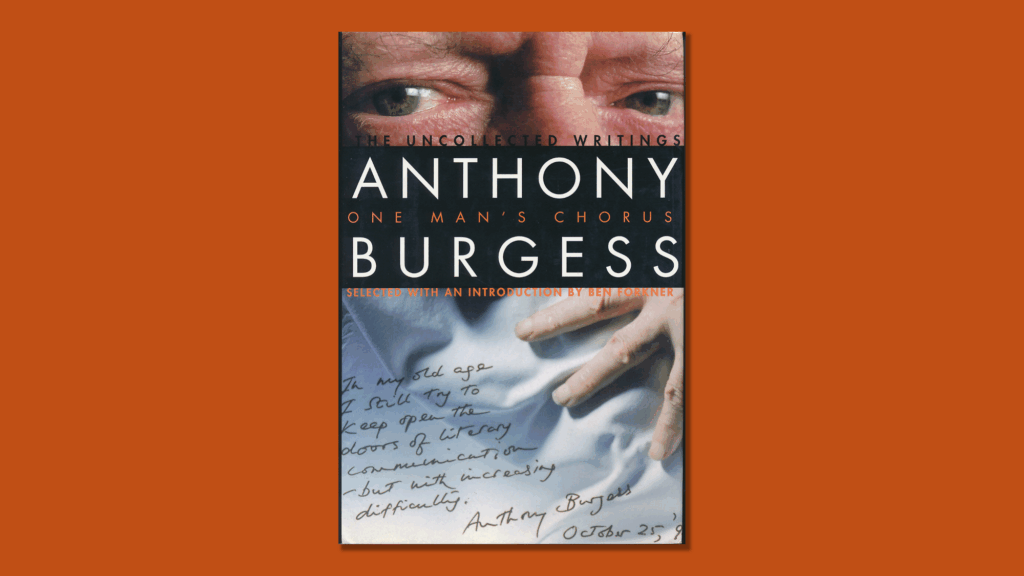

This memoir of Anthony Burgess appeared as the introduction to One Man’s Chorus: The Uncollected Writings, a selection of Burgess’s journalism, edited by Ben Forkner and published in New York by Carroll & Graf in 1998. We are grateful to Ben Forkner for kindly giving permission to reproduce his introduction here.

The paradox in our title One Man’s Chorus can be easily unknotted when we consider the multitude of different voices Anthony Burgess could apparently summon at will, whatever the occasion or mode of expression demanded. Of course it is the singular resonance of the voice behind the voices that cannot be forgotten by anyone who ever heard the man himself speak in the flesh. And since the writing in One Man’s Chorus is as much a vocal as a verbal performance, that voice deserves to be evoked before anything else.

I first met him in 1969 when I was a young graduate student of literature, burdened by books, the toil of learning, and too many hours bent over works of scholarship that did not always make the blood throb with delight. The year Anthony Burgess arrived on campus, I was spending most of my time in the underground depths of the library. The sound of my own footsteps echoed behind me as I shut the door of a private carrel as impenetrable as a tomb. It was difficult not to feel buried in an ivory tower, with the fear that life and literature were now divided against each other for good. The fear would fade in the classrooms because I was fortunate to have excellent teachers who had crafty methods, and years of experience, in awakening the dead. During that same year I had been awakened too, and impressed, by several well-known writers invited to the university to read their works. But too often when these writers stopped reading and began answering questions their voices lost their vigor and assurance. They seemed worn out with the effort, relieved to relax from the strain of literary perfection and to fall back into the small talk of the ordinary stuttering world.

Anthony Burgess belonged to a different race of writer and speaker altogether. The voice that radiated creative fire and conviction while he read from his writing went right on radiating when he put the book down and addressed the present moment. He could not be worn out (as we were to learn one memorable day), and the spell that the recital of his written words had cast during that first reading continued unabated as he held forth throughout the hand-shakings, receptions, official dinners, and late-night drinking sessions that followed. The holding forth lasted not for a few days only, but during the entire month of his stay. For most of us, certainly for most of the tomb-stiff graduate students, this demonstration left us dismayed and thrilled at the same time. We were dismayed because we knew we could never hope to match the tremendous energy and erudition of the man, even if we buried ourselves in the library for a lifetime, thrilled because this was the first time we had ever experienced the sheer electric passion human speech can convey in the mouth of a master. Here was the inspired eloquence his novels are filled with, the immense culture, the outrageous wit, the oddity and pithiness of phrase, the effortless improvisation on any theme under the sun and moon. Places he had visited or lived in, the world’s languages, politicians of every stripe and smell, songs from the whole history of Broadway and the English music hall, poetry from any time and place, invariably illustrated from memory with entire stanzas: the range of his interests and the depth of his knowledge seemed to have no limits.

The explosive shock of these displays might have left his increasingly captive audience not only filled with awe and envy, but stunned into silence for good. Whenever he lectured in a classroom this was in fact often the case. On the day that has now become a legend on the campus, he had been invited to teach five different courses, not on general matters of his choice but on the scheduled topics of the required syllabus. These courses were given by five different professors, each one a highly regarded specialist in his field. The topics ranged from an account of Chaucer’s scientific knowledge in a specific passage from ‘The House of Fame’ on up to the problem of Celtic myth in Joyce’s Ulysses. A number of more arcane mysteries were to be demystified in between. Whether or not this was a plot by certain jealous professors is impossible to prove. Certainly it was not expected that he would accept all the invitations. An ambitious graduate student would not have signed up for more than two of these courses on the same day.

Burgess of course, without batting an eye, transformed what would have been a gruelling death march through a day of duty for a normal academic mortal into a one-man parade of spectacular virtuosity. A small group of us, joined by a few of the younger professors, followed him from class to class. We were dazzled, even the crusty old Miltonian whose eyes were moist when the lecture in his class came to an end with a long passage from Areopagitica quoted from memory (always from memory). We had all been given a valuable lesson. Literature did not mock the grave because it was printed on the page, but because it could be carried around alive in the brain. After five hours of uninterrupted brilliance, without a hesitation or a false note to mar the performance, no professor or student dared or desired to say a word. In a lesser man, this would have been enough. But we were to learn quickly that Burgess never talked for triumph, and that he took too much delight in the company of others to confine his energies to the classroom, or to allow the electroshocked captives therein to remain tongue-tied for long.

Above all he loved to please, to entertain. The mischief in his voice was contagious, and no table where he was sitting was allowed to grow glum or grim, much less dull. There was a great deal of the showman in his facial expressions and in the sudden gesticulations of his hands, and a great deal of theatrical skill in the ease with which he modulated tones and shifted accents. He parodied, he mimicked, and he joked. Charles Dickens and Groucho Marx joined the party. And he sang, in all the voices, choralling through time and across the ocean. He would break into Rodgers and Hart or Gilbert and Sullivan or a ribald Scottish ballad at the drop of a hat. He relished the thrust and challenge of free speech made freer by those who were willing to match him drink for drink. I learned later that this was the kind of jousting once prized in Dublin pubs, and that his upbringing in the Irish streets of Manchester before the war had helped hone his reflexes of sharp retort to a razor edge.

As graduate students, wary and often subdued, we were won over entirely by the hearty spirit of derisiveness, especially when the powers of the earth were evoked. If disrespect was considered by certain well-paid professors a weakness in a scholar and a gentleman, and they could well see he was both, it was a weakness we admired, especially since it was always based, verifiably, and amusingly, on the exact fact. Burgess never sneered, but he could not resist the pomposity-pricking anecdote about great men (and women), and we loved him for his lack of resistance. Laughter was the rule, the only rule to be taken seriously. Late at night there might be sudden flights of fury and wild plunges of pessimism, but these were part of the overall enchantment. I never detected much bitterness in his despair at the world’s folly, and self-pity was not in his nature. Somehow even the darkest doomsday pronouncements were full of humor. The end result of human history might be tragic, but human nature itself was essentially comic. When Anthony talked the road to hell was paved with banana peels.

For those of us who had the chance to hear him talk, One Man’s Chorus is a tape recorder or telephone into the past; for those who did not have that chance, they can rest assured that the essays in One Man’s Chorus capture the speaking voice, voices, to a syllable, or rather, I can hear him chide over my shoulder, to a phoneme, or is it allophone. Would that he were actually standing by my side to set me right. Still, we can be thankful that the learning and the exuberance of the living man are here on every page. There is more, however. Another quality of his speech that needs to be singled out has something to do with the underlying coherence of his thinking, whatever the subject: a tough-minded logic or reasonableness that can be found in everything he wrote as well, even when the writing was done once, in a hurry, and never revised. This is the greater miracle of the Burgess legacy, not so much that he possessed the gift of speaking in tongues, in person and in print, but the fact that the tongue-speaking was always intelligible and to the point.

Mr Enderby, the dyspeptic poet whom Burgess created but could not kill, once wrote a poem with the line ‘the thought that wove it never dropped a stitch.’ This was the case when Anthony Burgess spoke, though stitch-making is not the only metaphor that comes to mind. The words spilled out, but they spilled out in perfect order, in patterns with a purpose. The combination of reckless improvisation and lucidity of thought was, and is, astonishing. He had the gift of going at once to the heart of the matter, along with the rarer gift of making a single statement comprise a lifetime’s philosophy. A five-minute comment over a glass of beer had the polish of a printed paragraph, and every line of One Man’s Chorus bubbles up, champagne-like, with the freshness of the moment. It was said of Samuel Johnson’s sentences that even in the heat of argument they left the tongue fully formed; they might glow with the heat, but they cooled at once into hard iron. Burgess admired Johnson, but unlike Johnson, he always stopped short of the oracular. Burgess was a committed individualist who had lived through World War II, and who had had his fill of causes and castes. He was a novelist, not a spokesman, and he shunned the robe of the pontiff like a poisoned shirt. Here too, the young graduate student would learn a valuable lesson. However well-rounded and definitive the sentences that unrolled into the air, something in the sly sidewiseness of the eyes gave off the warning not to take things too seriously, and not to be taken in by false completeness. There was always more to be said, more to be written. Endless time was the essential condition of truth, and as long as there was time left, the final sentence would have to wait.

Time, however, in the busy life of Burgess was often more a problem than a promise. He called his first collection of journalistic essays Urgent Copy, a title that points to the pressures of writing against a deadline. The same title could apply to most of One Man’s Chorus. Several of the shorter essays, in fact, were actually composed as they were dictated to newspaper offices in London and Rome on the spur of the moment over the phone. They were then typed up from the recording, and the typescripts mailed back to the Burgess home. More often, he would type up the essays himself. And here too the words apparently flowed straight from the inner mind (always at a high tide of activity) directly to the published page. I saw him work on one of these essays in the lobby of a hotel. I had come by to take him to lunch, and was supposed to meet him in the bar-room. When I entered the lobby had been taken over by a tour group, and the bar-room was closed. To calm the disgruntled tourists drinks were being noisily served in the lobby itself. I tracked him down quickly by the sound of the typewriter and by the smoke signal rising above the crowd from the eternal panetella. There he was in a corner, sitting at a small table. The keys clanged, the roller turned, the carriage slammed to the right, the bell rang, the smoke puffed upward. The Burgess engine was at work. A London newspaper had called him earlier in the morning and had reminded him of an article that had to go to press that very day. I fobbed myself off as a tourist, took a free drink, and waited while he typed. He seemed oblivious to everything but the rhythms he himself was making. The hammering on the keys was steady, sure, professional. He could have been a skilled carpenter nailing in a roof. As the pages left the typewriter, his wife Liana picked them up and put them into an envelope. The article was mailed to England on our way to lunch. All in a morning’s work, and like the carpenter’s roof, made to last.

I insist on the vocal, or conversational element in these essays, and on the concentration Burgess could bring to bear on the task at hand, because he was often surprised when he was asked in interviews how he was able to write so much, and in so many different genres. The quality of the writing he was prepared to defend, if legitimately attacked, but how could he respond except with shrugs and chagrin to the charges of doing something well too often. The answer, I think, lies in his devotion to the craft he had chosen, a radical, almost puritanical devotion that made him exert all his powers whenever words were concerned. A carpenter will not mishandle a plank of good wood on or off the weekly job. For Burgess there was a mystical bond between the words he wrote and the words he spoke. To neglect or minimize either act was to somehow deny the entire faith. I once asked him if he thought Homer spoke Homerically. He answered that he could not have done otherwise. For Burgess the possibility was an absurd contradiction, as it was not for the other writers I listened to as a graduate student. I wonder, in fact, if the memory of his conversational voices will one day bring renewed attention to the wonders of his written work, or perhaps it will be the other way around. What other writer could have composed the novel-poem Byrne on his deathbed had not one of the voices in his head been in the habit for years of speaking every day to itself in wryly rhymed ironic verse.

One Man’s Chorus obviously does not represent the full structural range of his verbal art, the expansive multilinear narration of Earthly Powers, or the complex architecture of The End of the World News or Napoleon Symphony. None of the essays in One Man’s Chorus, nor those in his two earlier collections, Urgent Copy and Homage to Qwert Yuiop, were composed to hold the center stage. They were written quickly, for the day’s purpose, as candid commentary on any odd subject of the hour or the week. Three solid thick volumes of shorter pieces, however, by the same Burgess who filled the longer works with brio and brightness in every line, cannot in any sense be thought of as less than a major part of the immense opera of living English he left to the world. This is one more reason why the word chorus strikes the right note, or chord, in our title. These essays are not by any means the whole work, but without them the whole work would be less than complete.

This said, we should not be surprised to find many of the preoccupations of the fiction echoing throughout One Man’s Chorus: a serial chorus, if we like, of the main Burgessian themes: human life as a perennial dramatic action, propelled by the same old Manichean cycles of conflict; the power and pleasure of music, high and low (for everyone’s ‘depth of brow’ as he himself put it); the great creative, destructive dance of the sexes, on and off the stage; the necessity of moral judgment in a world of political doubletalk and journalistic cowardice; the willingness of the independent voice to address the ultimate purpose of civilisation; the pure existential joy of making use of the whole harmonic verbal register. Oddly, for all these choral manifestations, here and elsewhere, Burgess seldom wrote directly for the theater. And yet what other modern novelist has looked at humanity with more dramatic delight and theatrical expertise than Burgess in his prose fiction.

The delight, the expertise, the old energy, the full command of all the voices: these were still very much alive when I next saw Anthony Burgess and his wife Liana, some ten years after the first encounter. I was then teaching in the state university in Nantes, France, where he had been invited to give two lectures, one on Gerard Manley Hopkins, the other on T.S. Eliot. On the same occasion the city fathers had asked him to attend an official dinner, and to speak on the history of film and literature later that evening. Due to a train strike, all three talks were forced upon him on a single day: Hopkins in the morning, the official dinner at noon, Eliot in the afternoon, film and literature for the general public in the evening. The Burgess dazzle had not dimmed, despite a program that would have drained many a good man half his age. The city fathers had forgotten to plan a meal after the evening speech, so I suggested that Anthony and Liana come home for supper with me and my wife, Nadine. This was a rash suggestion because by then even the late night grocery stores were closed, and all we had were fresh farm eggs. Nadine is not easily flustered, and with her usual French (or Breton) flair, she whipped together a magnificent golden omelette within a few minutes. Coarse black pepper, fines herbes, and a bottle of wine did the rest. At the time I planned to make a short meal of it and to take Anthony and Liana back to their hotel to have at least one good night’s sleep before the early morning train. It was soon obvious that neither of them had considered this possibility for an instant. Liana matched her husband in every way, in readiness and conviviality. They were both looking forward to a long evening of conversation and company, the longer the better. Burgess once explained that he wrote his special brand of journalism, the kind of essays in One Man’s Chorus, as weekly lifelines back to England and English. He could accept geographical exile, but he feared exile from his native tongue like a deadly curse. He had been speaking French all afternoon, to journalists, intellectuals, students, and the various notables of Nantes. It was English he needed now; and even a French omelette in his eyes turned into a manifestation of Englishness, a sort of Hopkins epiphany of golden light spreading through the black depths of Nadine’s cast-iron skillet.

Hopkins, his favorite poet, was much on his mind that day. He had given a beautiful rendering of ‘The Windhover’ in the morning lecture, from memory of course. After the omelette, and the third glass of wine, I asked him if he knew other Hopkins poems by heart. He began to recite the sonnets slowly. He knew them all. Before he began the much longer ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’ I asked if I could turn on a tape recorder. After two hours the tape ran out. Two hours later I finally drove Liana and Anthony back to the hotel. They were both wide-awake and Anthony was singing one of the songs from Blooms of Dublin, the musical he made of Joyce’s Ulysses. It is difficult to believe that so much life can leave the world at once, all in one man. Fortunately we can still hear the voice in the books. And we can still celebrate the man. We had better, whenever we can, because there will never be another like him.

Text copyright (c) Ben Forkner, 1998. Reproduced with permission.