Anthony Burgess on Philip Larkin

-

Andrew Biswell

- 9th August 2022

-

category

- Blog Posts

Philip Larkin, who was born 100 years ago, was a twentieth-century novelist, poet and music critic whose place among the immortals remains uncertain. Although Larkin’s writing was popular during his lifetime, his reputation was badly damaged by the revelation, in a posthumous edition of his letters, that he was an enthusiastic racist and misogynist. His frank exchanges with friends such as Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest made some readers doubtful about the extent to which his poetry is infected by the hatreds and prejudices expressed in the letters.

Anthony Burgess joined the debate in 1993 when he reviewed Andrew Motion’s biography of Larkin for the Literary Review, which was edited at that time by his friend Auberon Waugh. He acknowledges The Whitsun Weddings as Larkin’s best book, but says very little about the two published novels, or the earlier or the later poetry.

Burgess’s review is a spirited piece of criticism which does not shy away from confronting the ‘extremism’ of Larkin’s political opinions. Burgess gets the measure of his man when he writes: ‘Larkin was xenophobic, went to Germany once because he had to pick up a prize, liked it, in so far as he liked anything, here.’

One other complaint is that very little happened to Larkin in the years when he worked as a university librarian, got drunk often and, rather less often, wrote poems. ‘The interesting things,’ Burgess comments, ‘happened in trousers, in pubs, and on paper.’

Burgess is keen to place Larkin within the wider canon of English poetry. Larkin, he writes, ‘wanted his work to be non-Empsonian, devoid of ambiguity, making a style out of despair.’ Summing up the biography and its subject, the review concludes: ‘This drunken abusive wanker was the real thing, and this is a real biography.’

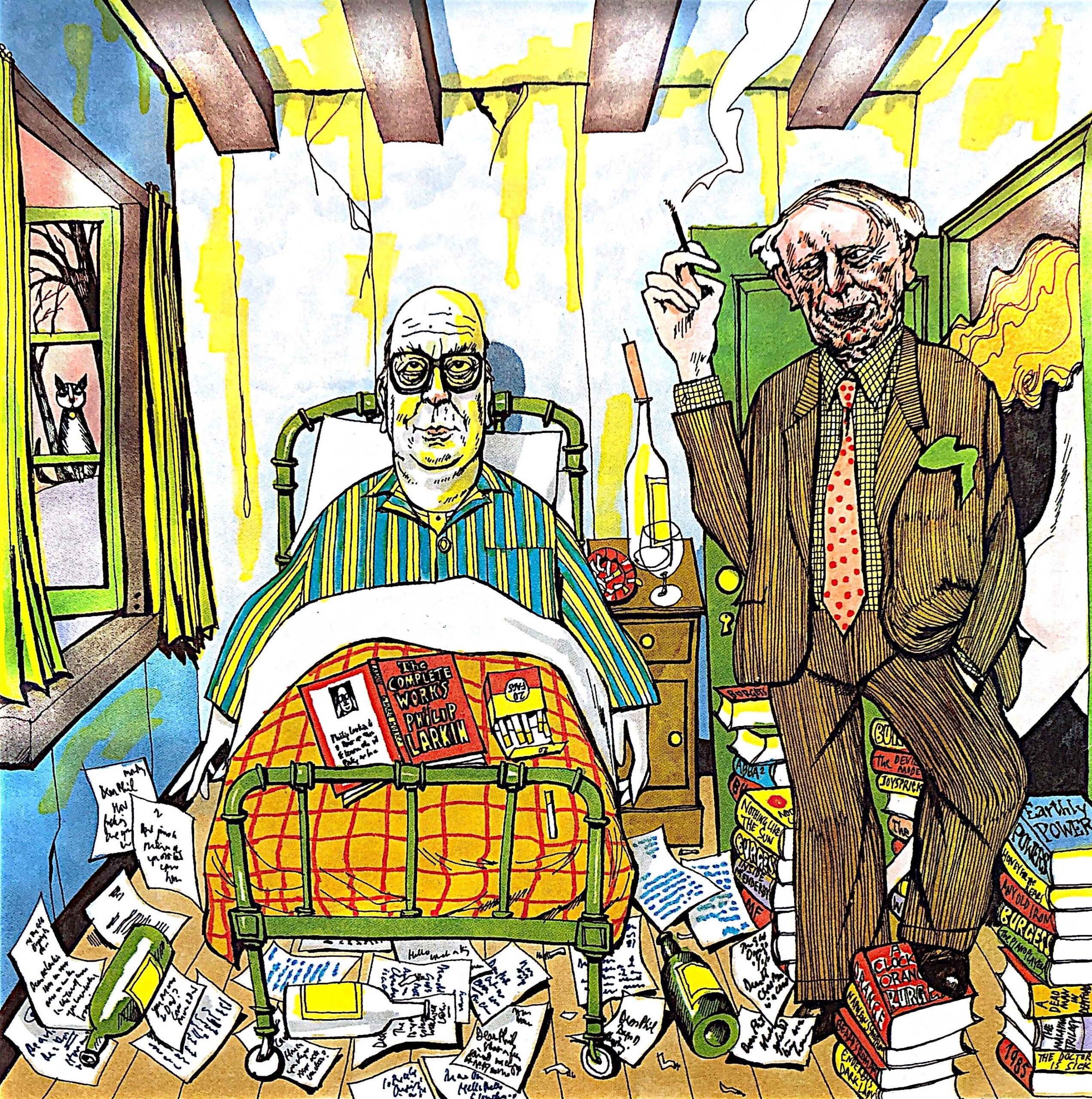

The front cover of the Literary Review for April 1993 contains a delightful illustration by William Rushton, in which Larkin is shown on his sickbed with a slim volume of his collected works, while Burgess stands in the corner smoking, with an enormous pile of his own books. A headline entices readers with the promise that ‘Burgess Passes Motion on Larkin.’

This was not the only occasion that Burgess commented on Philip Larkin and his poems. In the fourth of his T.S. Eliot Memorial Lectures, delivered at the University of Kent in 1980, Burgess offered some comments on why he thought W.H. Auden and Larkin were better poets than Eliot:

‘What I would suggest, in any seat of learning where the art of writing is studied (and it is increasingly), is that the hardest and the most rewarding school is one in which the rhythms, the intonation pattern — which, lacking a semantic core, seem aimless but do nevertheless form this separate art of music — be studied, because through them we can learn most about the nature of verbal rhythms, instead of setting our creative writing students exercises in the use of free verse, or the sestina, or even the sonnet. We should set them the Lorenz Hart task of taking a song, of taking a tune, and seeing what words, what speech rhythms, are implicit in it. This is a thought which springs out of an examination of Eliot’s own practice, which in one particular work, Sweeney Agonistes, he triumphantly demonstrated incredible possibilities — which in his own work were not fulfilled, but were to some extent in the work of Auden [and] in the work of Philip Larkin. What we wanted from Eliot and never got was an aesthetic.’

At the end of his lecture, Burgess went on to argue that Larkin’s poetry ‘draws out joyfully the prosodic potentialities of speech’ in ways that are comparable with jazz and popular song. This is clearly a style of poetry highly approved by Burgess.

The Foundation’s audio archive includes several cassettes of Burgess reading poetry aloud. There are three poems by Larkin in the collection: ‘How Distant’, ‘Broadcast’ and ‘Annus Mirabilis’. The anthology volume of They Wrote in English includes the same poems with a commentary.

Born in 1922, Larkin is the youngest poet to be included in the anthology. His poems follow a selection from the works of Francis Xavier Enderby (born 1917), and it must be conceded that Burgess is the only anthologist in history who has felt inclined to print Enderby’s poetry alongside Larkin’s while trying to define the canon of twentieth-century verse.