Anthony Burgess on Wimbledon

-

Andrew Biswell

- 8th July 2022

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess is well known for his anti-athletic approach to life, often expressed in heavy drinking and smoking, and for his general antipathy to sport. Apart from a commentary on the 1974 football World Cup for Time magazine, he had very little to say about sporting competitions. His autobiography records a single attendance at a Manchester City game when he was a boy. The main thing he noticed was the amount of swearing among the crowd.

It was surprising, then, to discover the typescript of an article about tennis in the Foundation’s journalism archive. The article, titled ‘Whither Wimbedon?’, was written in the summer of 1983, and it seems to have been intended for publication in an Italian newspaper.

Burgess recalls that he attended the annual lawn tennis championships in Wimbledon in 1972. He recollects the spectacle of wealthy people consuming strawberries with cream and champagne. Representing himself as a genuine fan of tennis, he is disdainful of fashionable spectators who are merely there to be seen. As a purist, he is more interested in the passion and drama of the sport.

Burgess demonstrates an unexpectedly detailed knowledge of tennis when he writes about watching a second-round men’s match on 26 June 1972, between the Czech player Jiří Hřebec and the Hungarian Szabolcs Baranyi, in which Hřebec was victorious. He remembers this encounter as having taken place on court number 14, and he claims to have been one of the few spectators, along with a small group of schoolchildren and ‘an army officer below field rank’. Burgess tells us that the authentic spirit of tennis is often seen in the smaller contests which remain totally unknown to people who follow the action on television. ‘Court 14 is a long way from Centre Court,’ he writes. ‘It is unhonoured by cameras and electronic scoreboards, and most of the habitués of Wimbledon don’t know where it is.’

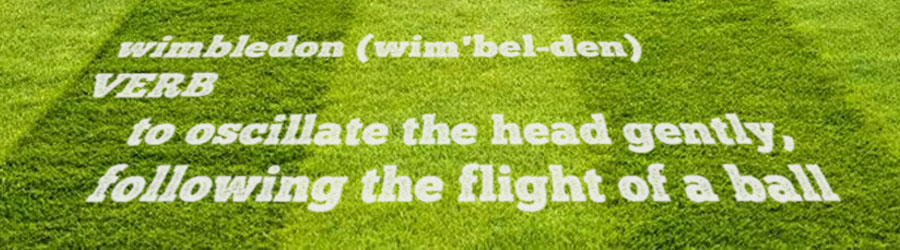

Never shy of blowing his own trumpet, Burgess informs the reader that he has also invented a verb, ‘to wimbledon’, and used it in his novel Earthly Powers: ‘She was in a shaded bedroom where a small electric fan sang and staidly wimbledoned.’ He defines this as ‘to oscillate the head gently, following the flight of a ball.’ In fact he had already used this verb much earlier in his 1961 novel The Worm and the Ring: ‘Suspicious heads wimbledoned towards him.’ This neologism is still waiting to be added to the database of the Oxford English Dictionary.

And there we might have left it, with a concluding paragraph about Burgess joining the list of literary tennis fans which includes Vladimir Nabokov, Claudia Rankine and Martin Amis, who was formerly the tennis correspondent of the London Evening Standard.

But there is a problem with the anecdote about Hřebec and Baranyi, and this changes the meaning of the article as a whole. It seems that Burgess could not have been in Wimbledon in June 1972, as he claimed. According to a series of letters sent to his London and New York agents, copies of which are in the Foundation’s archive, he spent the entire period between May and August 1972 living at 16a Piazza Santa Cecilia in Rome, working on a translation of Oedipus the King which was staged in Minneapolis later that year, and writing the first two sections of Napoleon Symphony.

Looking at the available evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that Burgess did not attend a match at Wimbledon on 26 June 1972, although it’s possible that he read about it in the newspapers, or listened to a match report on the BBC World Service. What is remarkable is that, in the pre-internet age, he was able to research the details and to give a plausible account of an event that he had not witnessed.

The article is a good example of Burgess deploying his powers as a novelist in what is ostensibly, at least, a non-fiction context. The same quality of expert faking is on display in the fictionalised dialogues and monologues in his biography of Ernest Hemingway. To any readers who are unfamiliar with Burgess’s tendency to inflate or distort reality, the Wimbledon affair offers a warning against taking his words at face value. But it would be a censorious umpire who judged his play to be the wrong side of the line.