Barrabooom: Bonfire Night

-

Will Carr

- 5th November 2013

-

category

- Blog Posts

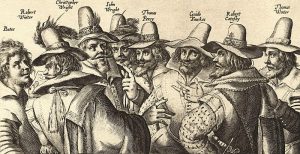

Anthony Burgess enjoyed bonfires and especially fireworks, relating in his autobiography his childhood attempts to manufacture them. In 1927, aged 10, he and his friend Eddie Carter, managed to produce ‘one rocket [that] went off with professional panache, though at an angle, and broke an upper window. Nowadays we would have been building a nuclear missile.’ However, the occasion for Bonfire Night itself was difficult for Anthony Burgess, and he remembered it as one of his first experiences of division and conflict. His Catholicism collided with the annual ritual, joyful burning of the so-called traitor Guido Fawkes:

‘[He] had tried to blow up Parliament on behalf of the English Catholics. Was it right for us children to enjoy the fireworks and the bonfire? Well, we could always imagine that the guy was really Henry VIII. And didn’t even the Protestant children treat their guy with a sort of protective love until the actual hour of conflagration? We pushed our guys round in old prams, cossetting them, begging for pennies for them.’ – Anthony Burgess, Urgent Copy, 1968

Bonfire Night first appeared in Burgess’s fiction in 1939, in his piece ‘Grief’, published in the Manchester University student magazine The Serpent. Winning the first prize of five guineas in the Sidebotham Prize, it is a short story in a modernist style, owing a lot to the work of James Joyce whom Burgess had first read aged fifteen or sixteen. Gerald and Leonard save their pocket money (like Burgess and his friend in his anecdote above) to purchase fireworks for Bonfire Night, but their plans are thwarted when an older, bigger boy throws a firecracker into their box and everything ignites:

‘Barraboom Leonard didn’t dare look at Gerald hissss as wheeee Gerald sssssstooood there wyowwwwwwww aiaiaiaimlessly thunderssssstrrrruck for brrrrroooommm neither Leonard nor Gerald had ever seen the other cry barrabooom’ – Anthony Burgess, ‘Grief’, 1939, quoted in The Real Life of Anthony Burgess by Andrew Biswell, 2005.

The fifth of November is the occasion in this story for a loss of innocence caused by the pointless violence of a bully: a pyrotechnic moment after which things are not quite the same again.

Burgess’s Catholicism was complex, uncertain and never simply expressed. While he did not identify with the radical terrorists Robert Catesby and Guy Fawkes, the explosions of Bonfire Night were for him not completely celebratory.

‘The guy could be ambivalent and everybody, Catholics and Protestants alike, could see his burning as a ritual rather than a revenge. But when history ceased to be ritual and became allegiance, the problem could not be solved in terms of love-hate … It was very difficult, and continued to be difficult. Religion got in the way of friendship, and, when the time came for love, love. Even language was a betrayer. If I wrote a poem or a story, which audience was a supposed to be addressing – the great Protestant one which Shakespeare and Milton had helped to make, or the smaller, despised, exotic one which was fed on the pamphlets of the Catholic Truth Society?’ – Anthony Burgess, Urgent Copy, 1968