Confessions of a Catman

-

Burgess Foundation

- 22nd October 2025

-

category

- Blog Posts

In this essay, originally published in the Spectator in March 1968, Anthony Burgess discusses the pros and cons of living with cats.

‘Dare to Be a Catman’ by Anthony Burgess

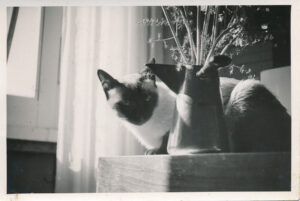

Cats only came properly into my life when, after six years of soldiering and two years of postwar mess (known officially as readjustment), I got a lecturing job with tied accommodation. This meant a home at last, so my wife and I went out and bought a young Siamese queen, seal-pointed, cross-eyed, kink-tailed, to put in it. We named her Lalage because she was a great talker (is Horace still read? I mean ‘Lalagen amabo, dulce loquentem.’ Our Lalage’s speech wasn’t sweet, though: it was harsh, rude, admonitory, demanding).

She had her own ideas. She liked to lap Amontillado out of a saucer and she suffered a regular Christmas hangover. She attached herself like a limpet to my wife and decided to hate me. She would come up to me purring and offer her small bullet-head to be rubbed. Then, as soon as I touched her, she would lash out and lacerate my hand. I always fell for this trick; I always wanted to believe that a change of heart was possible. But in nearly eleven years her heart never changed. She insisted on sleeping in the bed and lying, like a sword, between my wife and myself. In the night she would kick me on to the floor or scratch my back so viciously that I fell out of bed of my own accord. Only when she was on heat — and this always seemed to be a matter of volition, not of season — did she transfer her affections. She would leap on me and grapple herself to my chest, stiff as a furred board. If a tomcat responded to her crescendos of devilish heat-howls, she would beat him up and send him off crying. She died a virgin queen.

She was fantastically loyal to her mistress, but she had no real notion of morality. If she wanted something, she took it. If the cold remains of a stew stood on the stove in a saucepan, she would jump up, take off the lid with one paw, holding it like a cymbal, and then fish for a piece of meat with the other. She would then carefully replace the lid. She would steal other people’s kippers in pairs — one first to be hidden under her, our, bed for an after-lights-out dorm-feast, the other to be eaten on the spot. When she wanted a swig of sherry or burgundy (never claret), she would take it straight out of a guest’s glass, intermittently snarling over it like a lioness over a carcase.

My wife and I decided to go and live in Malaya. Naturally, Lalage had to go with us, though no British shipping line was willing to transport her. The Rotterdam-Lloyd people said she could bunk up with the bo’sun of the Willem Ruys, which meant being tied to the table-leg of his cabin. This wouldn’t really do, so he built her a wooden house and placed this on the crew deck. She decided to have a very loud heat, and this upset the more primitive of the Javanese deckhands. She got to Singapore to be greeted by a mass veterinary delegation; she got on the train to Kuala Kangsar. Eventually she settled, along with my wife and myself, in the state of Kelantan, right up against the Thai border. In a sense, she had come home. But she flew around the Federation a good deal — to Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh, Kangar, Taiping, Kuantan, Trengganu. All she asked was to be in bed with my wife and to get up occasionally for a lap or a visit to a box of sand.

She did well with the Malays, who adore cats. Normally a ball of fury if anyone other than her mistress tried to touch her, she would always allow Mat, the cook, to pick her up and carry her to her food. She seemed to have a race memory of the protocol applicable to Siamese royalty, which, if small enough, was always carried. Or else she understood the etymology of the Malay term berangkat, the special term for ‘go’ used for sultans and rajas and their ladies. If the Sultan of Johore walks down Regent Street, he is said to berangkat, while his subjects merely jalan. But the root of berangkat means ‘carry.’ In all that heat she was never too warm. When not in bed, she would sit by the servants’ charcoal fire, lifting her paws to the flames.

She became the nucleus of a domestic menagerie. The verandah was always open to the padang, and all day long it was busy with a mixed traffic of animals going to and from the living-room — a fierce cock called Regulus, all his hens, an otter, a turtle, sixteen ordinary cats (though, being so near Siam, their tails were kinked), an occasional visiting snake slithering to a cool rest under the refrigerator, a lizard or so. She maintained her dignity; her authority was never questioned. Regulus would fight the other cats for their food, but he kept away from Lalage. Even the wildest of these cats knew royalty when they saw it. And she was toughest of them all: she survived the feline enteritis that killed the entire cat population of the kampong; no cobra struck her; the packs of pye-dogs kept off. When we had to return to England, we saw that she would not survive six months of quarantine, so she was left with a worshipping Malay family. Her memory was going; she could clearly remember nobody except myself, whom she still felt constrained to hate. I swear, with the scars still on my body, that I gave her nothing but love. The love goes on, though it is a long time since we received a cable in Malay: ‘Lalage mati: Lalage dead.’ Horace’s future tense will do very well: Lalagen amabo, dulce loquentem.

Back in England, we have had other cats, and we rest now with two, one of which is grey and is called Dorian. He seems determined to give me the love which I never got from Lalage. He is always on my knee, and sometimes he attempts a sexual assault on my arm, gripping the scruff of my wrist to hold on better. I seem now to have developed a smell which appeals to tomcats. As for my wife, she has always known cat-language. On one occasion she made a small mistake in intonation when addressing a quite amiable cat. The cat, incredulous, made an interrogatory noise. My wife repeated her wow-wow remark, complete with solecism. The cat, with a more-in-sorrow-than-anger look, spat, scratched and ran away. On the whole, though, we get on very well with the entire tribe. I think we can call ourselves cat-people.

What is there in some people that leads them to cat-adoration, what is there in others that makes them abominate the entire furred race? There have been saintly loathers and devilish grovellers before whole purring baskets. I am sure, because of this, that cats have nothing to do with moral character. They go beyond good and evil and are hence probably closer to ultimate reality than the dogs we make in our own image, the horses we break, the cows we milk. We can’t imagine God as a dog, but He may well be a cat with (Old Possum’s words) an ineffable name. If there is an answer, it is probably a theological one. Credo in unum felem.

© International Anthony Burgess Foundation, 2025. All rights reserved. Not to be reprinted without permission.