Researching the Burgess collections: Amaury Garcia, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro

-

Amaury Garcia

- 20th January 2014

-

category

- Blog Posts

Amaury Garcia is a PhD candidate at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro (Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro), researching the life and work of Anthony Burgess. Amaury received a travel grant from the Burgess Foundation to support a trip to Manchester, where he has spent the last fortnight in the Burgess collections. Here is his account of his visit.

—————-

“What’s it going to be then, eh?” This was the question I asked myself after I had successfully finished writing my master’s dissertation, back in 2005. It was a comparative study between Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. By that time I had already fallen in love with Burgess’s oeuvre and with his magnetic character. So, I made up my mind to continue research on my favourite Mancunian.

At first I didn’t know which of his works to choose, as many of his books had made quite an impression on me. Andrew Biswell’s biography The Real Life of Anthony Burgess showed me a possibility. Biswell’s book was quite revealing and strengthened a notion I had been nurturing, that there couldn’t be only one Burgess. There were different ones, depending on where we looked. I then remembered that when I had read the Enderby novels I had a strong impression that I was faced with a somewhat darker side of Burgess’s character. Thus, I decided to carry out a comparative study between Burgess’s autobiography and Inside Mr. Enderby.

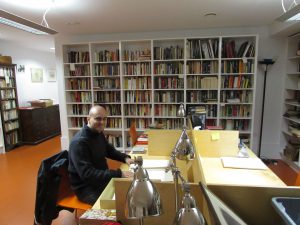

Having advanced with the theoretical aspects of my research, I felt that having access to Burgess’s personal archives would be of utmost importance to my work. Knowing the International Anthony Burgess Foundation held such archives, I decided to get in touch with the foundation’s director, Andrew Biswell. After a few e-mails, I sent him a proposal asking for the foundation to finance part of my research, more specifically a trip to Manchester, along with a two-week stay in the city, so that I could dig into Burgess’s archives. The proposal was accepted and here I am now, a student from Brazil, who has been given the opportunity not only of accessing precious material at the foundation but also of seeing and experiencing the native town of my favourite Mancunian.

One of the points I defend in my thesis is that the fictional discourse could be considered more powerful in its capability to affect readers than so-called factual discourses. We all know that autobiographies can’t really be said to be factual. However, I believe that when one reads an autobiography one basically seeks information. Hence, I tend to think of autobiographies as being factual. When one reads fiction, the point is quite different. At least this is what happens to me. When I read fiction I am open to be affected, to let go of myself and enter the minds of the characters who are presented to me, to live their lives, to feel their joy and sorrow or, in the words of Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, “to experience otherness”. I decided to compare Inside Mr. Enderby to Burgess’s autobiography because I felt that some of the topics he tackled in the latter were not only present in the former, but that they affected me more pungently through the reading of the Enderby novels.

Another theoretical aspect that informs my thesis is Roland Barthes’s notion of biographeme. Roughly, it means that one is compelled to write creatively about the author one loves, using traces found in the works (fictional or not) and documents of such an author that one is affected by as raw material. It means one describes the life of an author one admires through what this author has made one feel.

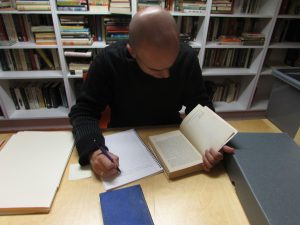

Having said that, I believe that the importance of having access to documents and especially drafts of texts written by Burgess for my work cannot be overemphasised. This is where the International Anthony Burgess Foundation has shown how important it is to keep the archives of an author in order and to provide scholars like myself with a chance to access them. I’ve found invaluable material which has offered so many new paths for me to follow.

Firstly, I was ushered into a room where one can see Burgess’s personal library along with many other personal objects he possessed. I was instantly affected by the sheer volume and variety of books held in the library. The shelves showed me many of the writers who had influenced Burgess, giving me, I think, a deeper understanding of the author I study. The first documents I perused were typescripts of an intended adaptation of the Enderby novels to the big screen. Burgess presented the hero in different ways, thus heightening other aspects of the character. Then, I was shown many of the obituaries and many reviews on the works I’m dealing with, all texts quite interesting for my research, of course. It took me a couple of days to go through those.

Then I got to some of the most revealing archives: many audio files. Some contain passages of Burgess reading from Inside Mr. Enderby and from Little Wilson and Big God. Listening to Burgess’s voice had quite a big effect on me, especially as he was reading from the works I’m dealing with. Some other audio files contain interviews with Burgess as well as with people who were around him. These showed a more emotional, somewhat tender side of the Mancunian that was unknown to me. The dramatised radio versions of the Enderby story were quite interesting too. They helped me, paradoxically it seems, visualise the hero more concretely, as I could hear “his” voice as he faced his troubles.

Every day of research at the Foundation I was shown something revealing. The last documents I saw are Burgess unpublished poems, some of them just rough drafts, containing his own illustrations. Many of these poems are translations of the sonnets by Giuseppe Gioachino Belli, the Italian poet. They are religious in nature, which links them to one of the main topics in the Enderby novels, namely Catholicism. Along with every document some new trace appears, adding layers and layers to the character I intend to describe in my thesis.

In addition, Will Carr and Andrew Biswell pointed some places around Manchester that have a connection with Burgess, such as the Xaverian College, the Church of the Holy Name and some streets where he lived as a boy and as a young man. I was able to visit them all and tried to imagine my beloved author walking down such streets, attending classes, studying and losing his faith. Such visits were very important. I have to say it’s a pity I’m staying here only for two weeks, because I’m sure there is still so much to be explored in the Foundation. I’ll have to go back to Brazil soon. But my experience here has profoundly enriched my research and my understanding of the life and work of Anthony Burgess.