The Banning of A Clockwork Orange

-

Andrew Biswell

- 5th April 2019

-

category

- Blog Posts

The re-release of the Clockwork Orange film in the United Kingdom (on 5 April 2019) provides an opportunity to revisit the turbulent history of Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic adaptation, which was first shown in New York in December 1971, with the British and European premieres taking place in January 1972.

To many people in Britain, Kubrick’s film is best known for its notoriety and lack of visibility. This story is already a familiar one. After A Clockwork Orange had been widely distributed in 1972 and 1973, the director took the decision to withdraw his own film in Britain, where he lived, but it remained available in all other territories where it had been released. This self-imposed ban remained in place until Kubrick’s death in 1999. Despite a proliferation of VHS copies smuggled across the Channel from mainland Europe, A Clockwork Orange was not legitimately screened in Britain between Kubrick’s suppression of his film in the mid-1970s and its cinematic re-release in 2000. One of the consequences for Anthony Burgess was that there was a ready audience for his stage version, A Clockwork Orange: A Play With Music, which received notable productions from the Royal Shakespeare Company and Northern Stage in the 1990s.

Looking into the archives, we have uncovered some new information about the reception history of Kubrick’s film.

The film was released in the United States, Germany, France, Italy, Japan and Australia, where it met with relatively little trouble from the censors. But it was banned in Spain, South Africa and Brazil — and there were further difficulties with the censorship authorities in Argentina, who insisted on cuts.

The British Board of Film Censorship (BBFC), as it was known until 1984, issued a certificate for A Clockwork Orange on 15 December 1971. Although the Board did not demand that any cuts should be made, the award of an X-certificate meant that the film could only be shown to people above the age of eighteen.

That would have been the end of the story as far as British cinema audiences were concerned, but for the existence of two little-known acts of parliament — the Cinematograph Acts of 1909 and 1952 — which empowered local authorities to prevent the screening of inflammatory films, at the discretion of town councillors.

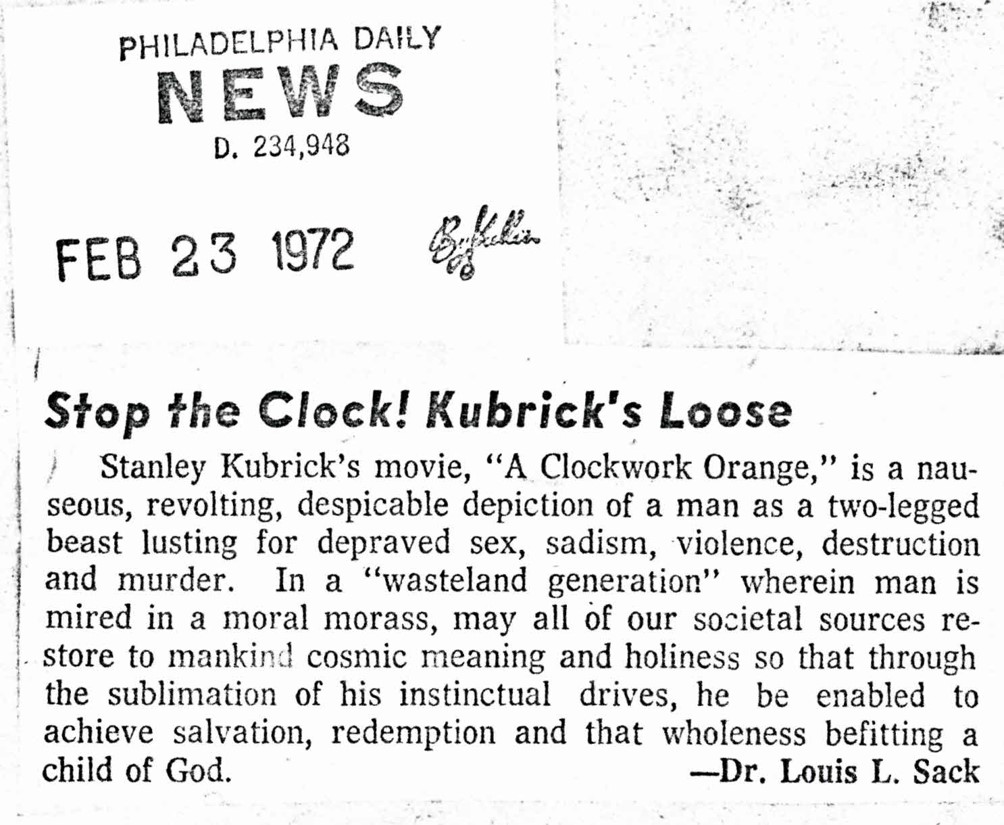

Following the appearance of sensational stories about delinquent youths in newspapers such as the Sun, Daily Telegraph and Daily Mail, published in the wake of the film’s UK release in 1972, a number of local councils in England refused to give permission for the film to be screened in their areas.

According to the available records, A Clockwork Orange was banned in Ashford Blackpool, Dorking, Esher, Hastings, Horley and Reigate. Jill Knight, the Conservative Member of Parliament for Edgbaston, campaigned unsuccessfully to have the film banned in the City of Birmingham. There was much correspondence between the BBFC and local councils in Leeds and Nottingham, where the authorities demanded private screenings of the film to determine whether or not it should be shown there.

One piece of correspondence from 1973 gives a strong flavour of the period. In a letter sent by recorded delivery to a cinema in Hastings on 7 February 1973, the Town Clerk of Hastings, Mr D. J. Taylor, wrote as follows:

I am instructed to give you notice in pursuance of Condition no. 13 of the licence which you hold under the Cinematograph Acts in respect of the above-named premises that the film entitled A Clockwork Orange shall not be exhibited in the premises on the respective grounds that, if exhibited, it would:

(a) offend against good taste or decency;

(b) be likely to encourage or incite crime or lead to disorder;

(c) be offensive to public feeling.

This was dark news for the cinema-goers of Hastings — but, fortunately, it was possible to board a train in Hastings and disembark ten minutes later in the Municipal Borough of Bexhill, where A Clockwork Orange could be viewed without restriction by anyone above the age of 18.

Now that A Clockwork Orange has been re-released in cinemas throughout the UK, it is likely that a more sober assessment of Kubrick’s work will be undertaken.

Here at the Burgess Foundation, we are wondering what view of the matter will be taken by the good people of Blackpool, Esher, Reigate and Hastings. Will public feeling continue to be offended? Will the exhibition of this film lead to disorder? Will it incite wanton acts of criminality among the young?

We hope that the Town Clerks of today will take a more moderate view than their counterparts in the 1970s, and that they will look on A Clockwork Orange as a classic work of modern cinema.