A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange is Anthony Burgess’s most famous novel and its impact on literary, musical and visual culture has been extensive. The novel is concerned with the conflict between the individual and the state, the punishment of young criminals, and the possibility or otherwise of redemption. The linguistic originality of the book, and the moral questions it raises, are as relevant now as they ever were.

- A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange on film

- A Clockwork Orange on stage

- The Music of A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange and Nadsat

- A Clockwork Orange and the Critics

- The Legacy of A Clockwork Orange

- The Podcast

The Music of A Clockwork Orange:

‘Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my Gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders. And then, a bird of like rarest spun heavenmetal, or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship, gravity all nonsense now, came the violin solo above all the other strings, and those strings were like a cage of silk round my bed. The flute and oboe bored, like worms of like platinum, into the thick toffee gold and silver. I was in such bliss, my brothers.’

– Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange (1962).

Alongside his literary work, Burgess wrote music across many genres and in many styles. His oeuvre includes symphonies, concertos, opera and musicals, chamber music including a great deal of work for solo piano, as well as a ballet suite, music for film, occasional pieces, songs and much more. He draws upon classical as well as jazz and popular music. Grounded in the tradition of tonality that spans the Baroque period through late 19th-century Romanticism and early 20th-century French Impressionism, Burgess’s music is strongly influenced by the works of Debussy and the English school of Elgar, Delius, Holst, Walton, and Vaughan Williams.

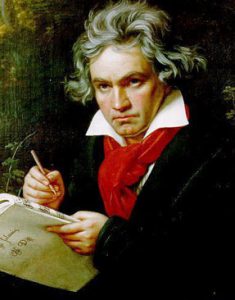

Works by real and imagined composers provide the soundtrack to fantasy, robbery and murder in A Clockwork Orange. Rather than a simple, and perhaps more obvious, soundtrack of pop music or rock and roll, long thought of by the establishment as a corrupting and immoral force among the developing teenage culture of the 1950s and 1960s, Burgess uses the work of Beethoven as a structural and aesthetic device. In choosing ‘the old Ludwig van’ as Alex’s music of choice, Burgess’s is presenting his anti-hero as cultured and intelligent. As Martin Amis notes in his introduction to the restored edition of A Clockwork Orange, Burgess’s choice of music in the novel betrays ‘the authorial insistence that the Beast would be susceptible to Beauty. At a stroke, and without sentimentality, Alex is decisively realigned. He has now been equipped with a soul, and even a suspicion of innocence’. When Ludovico’s Technique removes Alex’s love of music, it also removes his soul, something that Burgess highlights as an example of the moral degeneration of the state.

Burgess loved Beethoven’s music as much as Alex does. He wrote that, ‘I accepted the Beethoven symphony as a kind of musical ultimate, something that the composers of our own age could not aspire to […] His sonatas and symphonies were dramas, storm and stress, revelations of personal struggle and triumph. The Messiah from Bonn […] belonged to a world that was striving to make itself modern’. Burgess and his protagonist also share a loathing of popular music. When Alex enters a record shop in the novel, he looks at the ‘popdiscs’ and ‘teeny pop vesches’ with obvious disdain. Similarly, Burgess had no time for pop music, calling it ‘twanging nonsense’ and claiming that, ‘youth knows nothing about anything except a mass of clichés that for the most part, through the media of pop songs, are foisted on them by middle-aged entrepreneurs and exploiters who should know better’.

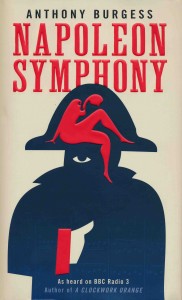

Burgess’s love of music does not only appear in A Clockwork Orange. Other novels are inspired by Burgess’s musical grounding. The Pianoplayers (1986) is inspired by Burgess’s father’s experiences playing the piano in pre-War Manchester; Earthly Powers (1980) describes the travails of a film composer; Byrne (1993), Burgess’s verse novel, tells the story of a hard-living Irish composer; and The Eve of St Venus (1964) started life as an operatic libretto. But it is Burgess’s love of Beethoven that gave him the most inspiration. Beethoven appears as a character in Mozart and the Wolfgang (1991) and in ‘Uncle Ludwig’, an unproduced film script about Beethoven’s relationship with his nephew. Perhaps most famously, the composer’s Eroica symphony provides the structure for Napoleon Symphony (1974), Burgess’s fictionalised life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Burgess’s dramatic version of this novel, Napoleon Rising, was broadcast for the first time by BBC Radio 3 in December 2012 and starred Toby Jones in the title role.