The Music of Anthony Burgess: Symphony in C

Explore Anthony Burgess’s Symphony in C below.

Symphony in C (first movement) by Anthony Burgess, performed by the Brown University Symphony Orchestra in 1997 and conducted by Paul Phillips.

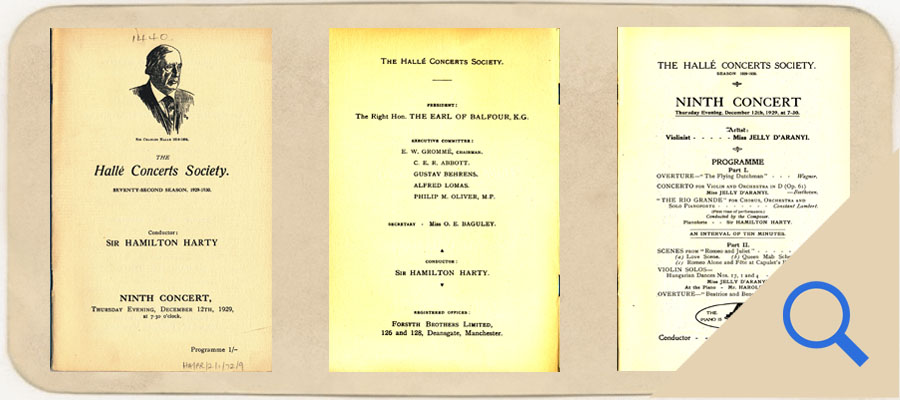

The programme for the concert given by the Halle Orchestra in Manchester on 12 December 1929 (first 12 pages of our scanned file featured here). With music by Wagner, Beethoven, Berlioz and Brahms, the centrepiece was the premiere of Constant Lambert’s The Rio Grande. Anthony Burgess attended this concert at the age of twelve with his father, and these experiences of orchestral music were formative in his development as a composer.

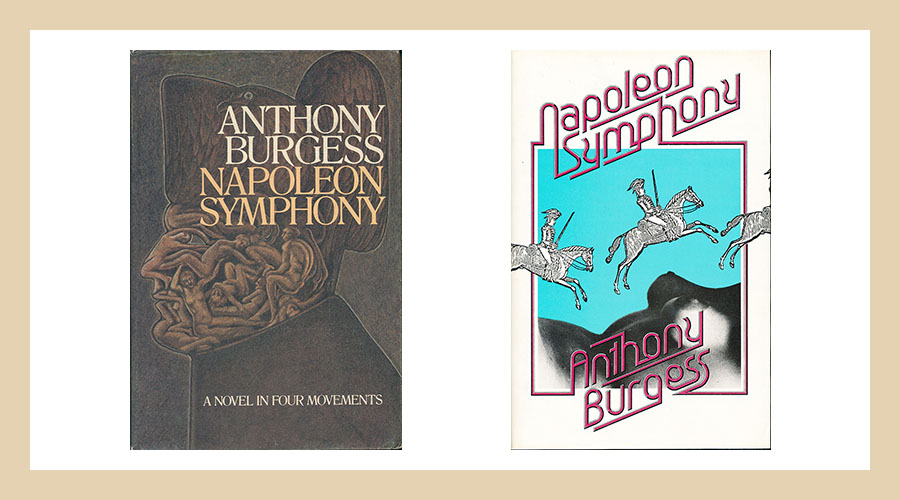

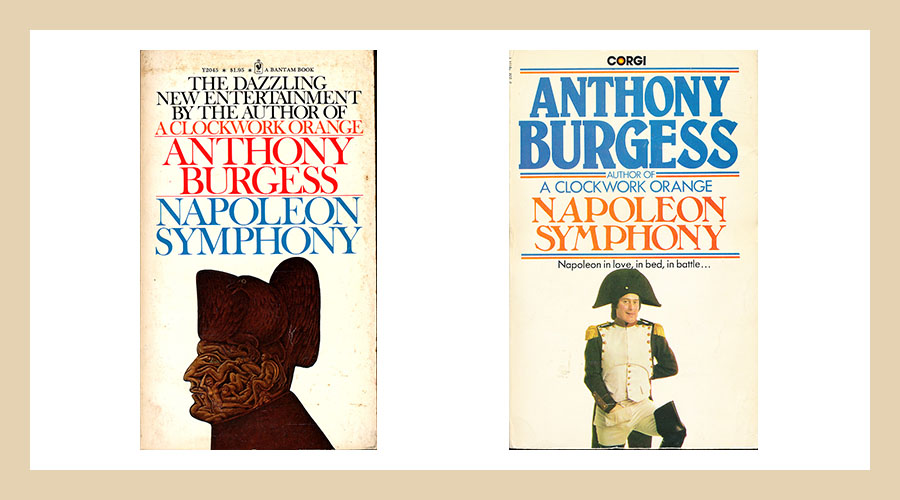

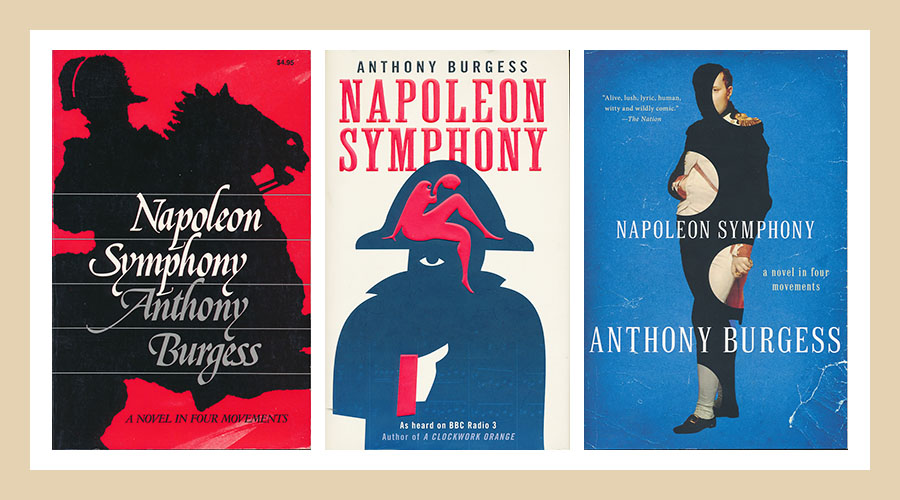

Anthony Burgess’s 1974 novel Napoleon Symphony, a rich, exciting, bawdy and funny novel that tells the story of Napoleon Bonaparte using the formal structure of Beethoven’s Third Symphony

Burgess tells the story of how his symphony came into being in the New York Times — a review of the performance appears at the end of the article.

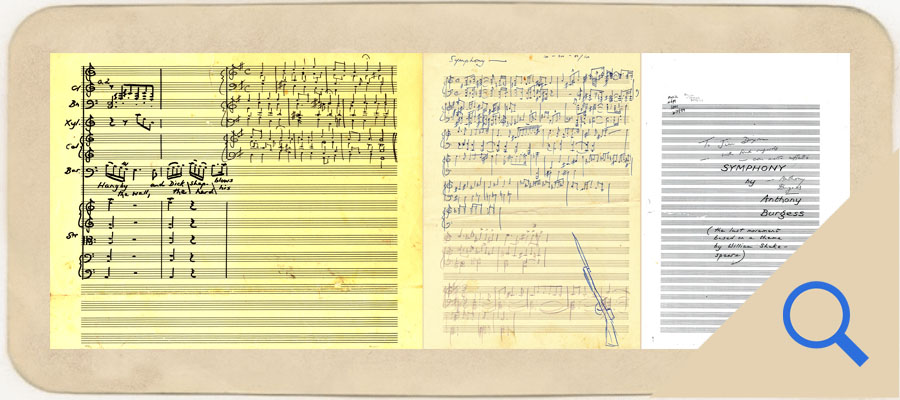

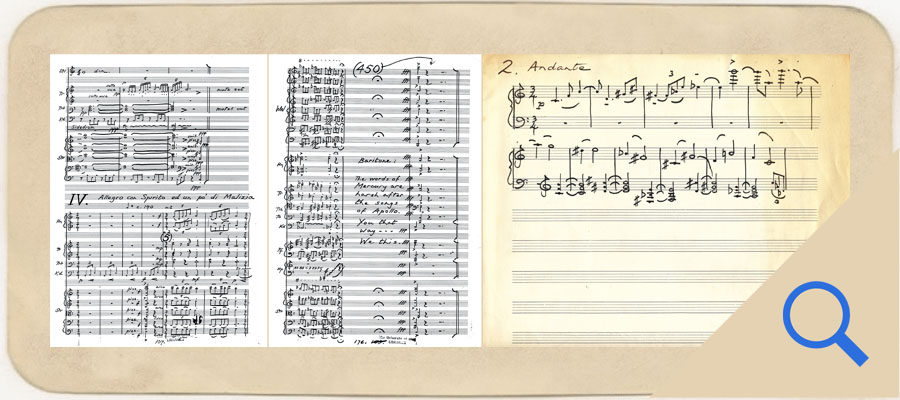

Pages from the manuscript score of Anthony Burgess’s symphony.

Symphony in C in context

Anthony Burgess sometimes described himself as a composer who wrote novels on the side.

Music was central to Burgess’s creative life. He received basic instruction in the piano and violin as a boy, attended concerts by the Halle Orchestra in the 1920s with his piano-playing father, and later worked as an arranger for a dance band in the Army Entertainment Corps during the Second World War. Although Burgess composed music throughout his adult life, his activities as a novelist kept him at the typewriter during the early part of his artistic career..

The turning point came in 1975, when James Dixon, conductor of the University of Iowa Orchestra, asked Burgess to write a symphony. Dixon had read Burgess’s novel Napoleon Symphony, structured around Beethoven’s third symphony, the Eroica, and he was intrigued by the verse epilogue which describes the author’s dream of giving ‘symphonic shape to verbal narrative’. Dixon offered to perform an orchestral work by Burgess if one existed.

Burgess claimed to have written two full-scale symphonies for orchestra by this time. Symphony No. 1 was, according to his account, destroyed by German bombs during the Second World War, although a piano reduction survives. The score of Symphony No. 2 was lost by Radio Malaya after Burgess sent it to them in 1956. There is no record of either of these two symphonies being performed.

Having received the invitation from James Dixon, he set about composing a new piece, titled Symphony in C.

The 1975 symphony is in four movements, with a duration of 35 minutes. Stylistically conservative for the time, it is full of colour, texture, energy and dynamism and is influenced by the work of Jean Sibelius and Dmitri Shostakovich, to whom the third movement is dedicated.

The final movement ends with spoken lines from Shakespeare’s play Love’s Labours Lost: ‘The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo.’ In Burgess’s description of the conclusion, ‘The orchestra then plays a single fortissimo chord of C major and everyone goes off for a drink.’

Not having heard his orchestral music played before, Burgess wrote: ‘I had written over thirty books, but this was the truly great artistic moment. I wished my father had been present. It would have been a filial fulfilment of his own youthful dreams.’

Symphony in C is one of Burgess’s most ambitious compositions and it represents a high point in his journey as a musician. After the work was received favourably by the audience and reviewed positively in the New York Times, Burgess returned to composing with renewed enthusiasm. After the performance in Iowa in 1975, he became more confident and prolific in his musical writing until the end of his life.