A Clockwork Orange on Stage

Welcome to our online exhibition exploring A Clockwork Orange on stage. Find out about the theatrical version of the famous novel, and explore images from some of the many theatre adaptations from around the world.

- A Clockwork Orange on Stage

- Bretton Hall, Bonn, Barbican

- Edinburgh, Chicago, Newcastle

- Saarbrücken, Los Angeles, Paris

- Camden, Glasgow, Stratford

- Tokyo, Toronto, Soho

- Cambridge, Moscow, New York, Liverpool

- Weimar, Mexico City, Regensberg

- Singapore, Leipzig

A Clockwork Orange on Stage:

After the publication of A Clockwork Orange in 1962, it did not take long for the dramatic possibilities of Burgess’s novel to be explored.

The first partial adaptation of A Clockwork Orange took place on BBC television. Burgess discussed his work with the writer Kenneth Allsop on the Tonight programme on 17 May 1962, three days after the novel had been published, and the feature was accompanied by a dramatic presentation. No recording of this live broadcast has survived, but Burgess recalled it in the second volume of his memoirs, You’ve Had Your Time:

‘They dramatized much of the first chapter of the book very effectively and made more of the language than the theme. I showed myself to be an adequate television performer.’

He seems to have been pleased by this rendering of his novel by actors, yet there were no further adaptations of A Clockwork Orange until Andy Warhol’s piratical film version Vinyl in 1965; nor again until Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film. Burgess performed his own text for the Caedmon vinyl LP recorded in 1973, reading three chapters from the novel and presenting Alex with the broad accent of his own youth in Manchester. But it was not until 1976 that the first stage adaptation of A Clockwork Orange emerged.

JOHN GODBER’S A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

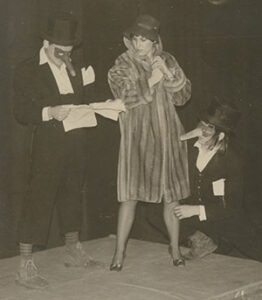

John Godber was an undergraduate student at Bretton Hall College of Education in West Yorkshire in 1975, and he presented an adaptation of A Clockwork Orange as a piece of assessed work for his drama course on 17 November 1976. This is the first known performance of a stage adaptation, and the production was later revived in Edinburgh and London. John Godber would later become an acclaimed screenwriter and playwright, artistic director of Hull Truck Theatre, and later the creative director of Theatre Royal Wakefield.

John Godber was an undergraduate student at Bretton Hall College of Education in West Yorkshire in 1975, and he presented an adaptation of A Clockwork Orange as a piece of assessed work for his drama course on 17 November 1976. This is the first known performance of a stage adaptation, and the production was later revived in Edinburgh and London. John Godber would later become an acclaimed screenwriter and playwright, artistic director of Hull Truck Theatre, and later the creative director of Theatre Royal Wakefield.

A Clockwork Orange was John Godber’s first play. He was originally alerted to the potential for an adaptation by Stanley Kubrick’s film, and he saw its influence on youth culture in Yorkshire in the early 1970s, with media reports of copy-cat street violence and Leeds United football hooligans dressing up as droogs. He was also drawn to the figure of Anthony Burgess himself, who was becoming a regular fixture on TV chat shows such as Parkinson.

Godber was particularly interested in the challenge of rendering the physical action of the novel into a language for the stage. The solution he found was to avoid any actual physical violence, and to create theatrical effects through large, symbolic gestures and energetic choreography, giving the impression of physical violence without presenting it literally.

Godber’s script contains a great deal of Nadsat dialogue and sticks closely to the plot of Burgess’s original text. The set was simple and props were very limited. Full of dynamism, the action of the play races along in a single act, punctuated by moments of extreme, exaggerated action. The visceral experience is heightened by screaming and vomiting, and there are demands in the stage directions to ‘make the audience cringe.’

One of the most distinctive aspects of the adaptation is that the Alex character is played by two actors: a young, violent, pre-Ludovico Technique Alex, and an older, wheelchair-bound, post-Ludovico Alex, who acts as a static Narrator, on stage throughout the action and ostensibly recovering from his treatment — until the end of the play, when his entrance on two feet and in full droog costume, ready for ultraviolence, is designed to create a moment of unexpected menace.

Have YOU got images from your stage production of A Clockwork Orange that you’d like featured in this exhibition? Get in touch.

A PLAY WITH MUSIC

While Burgess did not see John Godber’s adaptation performed, it seems that he read the script when a copy was sent to him by his agent in 1985. Later that year Burgess created his own adaptation, titled A Clockwork Orange: A Play With Music.

Burgess writes in his introduction that his play ‘is not grand opera. It is a little play which any group may perform.’ It has a limited cast, with opportunities for doubling up, and a minimal set and props, and the action is presented through a series of carefully arranged tableaux. Burgess’s stark images, stylisation and elaborate choreography address the problem of rendering ultra-violence on stage.

Burgess is keen to stress in his introduction that, unlike the Kubrick film, his adaptation ‘draws on the entirety of the book, presenting at the end a hooligan hero who is now growing up, falling in love, proposing a decent bourgeois life with a wife and family, and consoling us with the doctrine that aggression is an aspect of adolescence which maturity rejects.’ The final song in A Play with Music is a hymn to freedom of choice, with new words set to the tune of Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’. This is interrupted by ‘A man bearded like Stanley Kubrick [who] comes on playing, in exquisite counterpoint, “Singin’ in the Rain” on the trumpet. He is kicked off the stage.’

Burgess’s musical numbers convey the black humour of his novel. There are also excerpts from classical repertoire, mainly Beethoven, though Burgess is anxious not to insist too strongly on the musical proficiency of the players: ‘Beethoven is long out of copyright and may be freely banged around on a piano with whatever percussion suggests itself’.

Start browsing A Clockwork Orange on Stage

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE 2004

An expanded version of Play with Music, under the new title A Clockwork Orange 2004, was premiered by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Barbican Theatre in London in 1990. The director was Ron Daniels, who added material directly from the novel, both in dialogue and in Alex’s addresses to the audience. Some of the lyrics from Burgess’s musical numbers remained as spoken verse, and a new soundtrack was composed for the production by Bono and The Edge from the band U2.

The RSC production starred Phil Daniels as Alex, and his performance (choreographed by Arlene Phillips) was praised as ‘spidery and energetic’. The brooding set design by Richard Hudson created an atmosphere of menace. However, the production was not popular with critics or with Burgess himself, who described the music as ‘neo-wallpaper’. Following a transfer to the Royalty Theatre in London, the West End revival closed after a month.

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, 1988 to 2020

Burgess’s own adaptation, A Clockwork Orange: A Play with Music, is the one which has endured. John Godber’s adaptation remains unpublished and has not been revived since 1984, and there have been been no full-scale revivals of A Clockwork Orange 2004 in English, although this version is well-known in Germany.

Burgess’s own adaptation, A Clockwork Orange: A Play with Music, is the one which has endured. John Godber’s adaptation remains unpublished and has not been revived since 1984, and there have been been no full-scale revivals of A Clockwork Orange 2004 in English, although this version is well-known in Germany.

The first German version of A Play with Music took place in at the Schauspielhaus in Bonn, in 1988, in a translation by Harald Mueller. Original music was composed by the punk band Die Toten Hosen, who performed on stage as part of the show: their hit song ‘Hier Kommt Alex’ was taken from this production.

It was not until 1992 that the first documented performance of A Play With Music took place in English, presented by TAG Theatre in Glasgow, directed by Tony Graham. The sets and poster were designed by Alasdair Gray (whose novel Lanark Burgess had admiringly blurbed) and the play was choreographed by Andrew Howitt. This minimalist production toured regional theatres in Scotland, and Burgess was photographed with the cast during the Edinburgh leg of the tour in November 1992.

In 1995, two years after Burgess’s death, A Play With Music was revived by Northern Stage at the Newcastle Playhouse. Directed by Alan Lyddiard, the production toured widely around Britain for five years. Sean O’Brien reviewed this production for the Times Literary Supplement, finding it ‘insistently watchable’, with high praise for the actor Andrew Howard as Alex. All stage productions seem to depend for their success on the charisma of the actor in this leading role, who is on stage throughout Burgess’s adaptation.

A Clockwork Orange: A Play with Music was first presented with Burgess’s songs in 2000 by Fabulous and Ridiculous Theater in Austin, Texas, directed by Anna Catherine Rutledge. The songs did not receive their European premiere until a concert performance in Manchester in 2012. Since then, there have been various serious and successful attempts to make Burgess’s music more prominent, with a 2017 BBC radio production featuring the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra at the University of Hull, as part of the UK City of Culture celebrations. This was followed in 2018 by a major production at Liverpool Everyman, directed by Nick Bagnall and with Burgess’s music used in full, arranged by James Fortune and Peter Mitchell.

Nearly 300 productions of Play with Music were authorised by Anthony Burgess’s estate between 1995 and 2020. Around a fifth of these were amateur productions, and there is a wide range in scale, from school and village-hall productions to major international tours, some of which have run for several years. The diversity of territories in which the play is performed has increased in recent times, with first presentations in Brazil, Mexico, Malta and Slovakia since 2018. A number of new adaptations have been made for the Theatre of Nations, Moscow (which has run since 2017) and Teater Ekamatra, Singapore, produced in 2019. The first ballet version of A Clockwork Orange is currently in development with the Jihočeské Divadlo company in Prague. It is clear that Burgess’s Play with Music is continuing to find new forms.

Nearly 300 productions of Play with Music were authorised by Anthony Burgess’s estate between 1995 and 2020. Around a fifth of these were amateur productions, and there is a wide range in scale, from school and village-hall productions to major international tours, some of which have run for several years. The diversity of territories in which the play is performed has increased in recent times, with first presentations in Brazil, Mexico, Malta and Slovakia since 2018. A number of new adaptations have been made for the Theatre of Nations, Moscow (which has run since 2017) and Teater Ekamatra, Singapore, produced in 2019. The first ballet version of A Clockwork Orange is currently in development with the Jihočeské Divadlo company in Prague. It is clear that Burgess’s Play with Music is continuing to find new forms.

A CONTINUING PREOCCUPATION

Anthony Burgess’s ‘little play which any group may perform’ has come a long way since the 1980s. He writes in the introduction: ‘it is my farewell to a preoccupation which has continued too long. I mean an enforced concern with a book which belongs very much to my past […] and which I would prefer to forget.’ This intention was complicated by Burgess’s involvement in subsequent productions of the play, and by his habit of giving interviews and writing newspaper articles about the novel and its various adaptations. The effect of publishing the dramatic text has been the opposite of a farewell: his stage version of A Clockwork Orange has allowed a multiplicity of new interpretations, bringing the ideas and questions of the story up to date with each new production. Informed by Burgess’s comic and musical vision, the dramatic version of A Clockwork Orange continues to appeal to the imaginations of producers and directors all over the world.