Dystopian Fiction

This resource places Anthony Burgess’s writing in the context of the other dystopian novels of the period.

- Dystopian Fiction

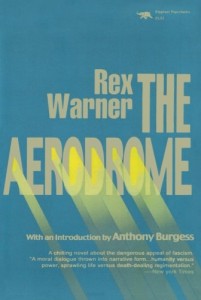

- Dystopias: Burgess’s Introduction to The Aerodrome by Rex Warner

- Dystopias: Burgess’s Favourite Dystopias

- Dystopias: An Extract from The Novel Now

- Dystopias: The Wanting Seed and the politics of fertility

- Dystopias: Burgess and George Orwell

- Dystopias: Burgess and Aldous Huxley

Dystopias: Burgess’s Introduction to The Aerodrome by Rex Warner:

In 1982, Burgess wrote a new introduction for Rex Warner’s The Aerodrome (1941). The novel itself reflected the turbulent politics of late-1930s Europe and depicted an England under siege from fascism. This novel impressed Burgess greatly, and can be seen to influence his own dystopian fiction. He eventually included Warner’s novel in Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English Since 1939 (1984), from where much of this introduction has been repurposed.

The Aerodrome appeared when the phoney war, or the Great Bore War as an Evelyn Waugh character called it, was over and the real war was beginning. For those of us engaged in fighting that war overseas it had to be a book that we merely heard of; the reading of it had to be long deferred. When I say ‘we’ I mean the members of what Arthur Koestler rather disdainfully called the Thoughtful Corporal Belt: ‘Read for pleasure, man,’ he wrote to an imagined representative of it, ‘and forget Joyce and Péguy.’ The fact is that there was not much time to read for pleasure, whatever Koestler meant by the term, but there had to be a time to try and learn what the war was all about, and this meant reading not only Joyce and Péguy (and Koestler for that matter) but also Kafka. When we started learning about Kafka we began also to learn about his British disciples. One of these was William Sansom, whose Fireman Flower was a brilliant exercise in the technique of Kafkaesque fantasy, and another was Rex Warner. The Wild Goose Chase, we read in such literary magazines as came our way, was a sedulous Kafka allegory with a strong political theme, but The Aerodrome was something different – an intensely original work which was Kafkaesque only in its use of allegory or large-size metaphor, whose subject-matter was too complex to be merely political and which, despite a strangeness relating it to Kafka, was very much in the English fictional tradition – meaning that it had three-dimensional characters (which Kafka does not have), humour and irony, and the smell of English earth.

I shall never forget my first reading of The Aerodrome. A thoughtful sergeant-major rather than a corporal, I was being sent home to England from Gibraltar on a derelict ship of French provenance with a monoglot Chinese crew. We slept on the deck and rats jumped over us all night long. Rats also turned up in savoury stews which, along with apple jam in cans the size of petrol drums, formed our three-week diet. There was a small ship’s library and in this I found three, repeat three, hardback copies of The Aerodrome. I stowed one in my kitbag and it became the first item in my post-war library. One of the others I devoured at once; I was, as I had expected, enthralled. I have reread The Aerodrome several times since and am, at each rereading, progressively more amazed at its prophetic qualities. Eight years older than Nineteen Eighty-Four, its claim to be regarded as a modern classic is a sound as that of Orwell’s novel, but one can see clearly why it has to be rescued periodically from popular opinion. It lacks the ‘popular’ elements of Orwell’s book — sex, overt brutality, explicit and recognisable ideology. It is subtle, ambiguous and restrained. It is also optimistic.

The basic scenario is a brilliant invention in itself. There is a thoroughly degenerate village, which represents fallen man. Men literally fall dead drunk, sluts fall backwards in the hedgerows; the local rat-catcher earns pints by biting off the heads of live ratlings. The pub is the centre of gruff or maudlin sodality; the manor house, with its decrepit squire, is the centre of secular authority; the church, with its intemperate rector, pretends to look after spiritual needs which are not much in evidence. This is the wretched or joyful human condition; the village is the human family with its palimpsest of interlinked atomic families. Outside the village there is a great aerodrome dedicated to cleanliness and efficiency. It is a self-sufficient totalitarian state with its eyes on the air not on the earth. The earth is dirty, and so are the men who work it and live off it; the future lies in the unsullied empyrean. The aerodrome absorbs the village, converting the manor house into a club and the rectory into a gymnasium, turning the agricultural land into airfields, exerting inhuman discipline on what was once a free society but itself, in the person of the Air Vice-Marshal, preaching the doctrine of freedom through self-control and the eschewal of brutal instinct. Arbeit macht frei.

Roy, the hero-narrator, is a much more convincing character than Orwell’s Winston Smith in that he is capable, which Winston Smith is not, of switching without exterior compulsion or brainwashing from a liberal to a totalitarian view and then back again. If no man in his right mind could voluntarily accept the principles of Ingsoc, there is something in all of us which finds the Air Vice-Marshal’s doctrine of non-attached working for the future fairly attractive. ‘What a record of confusion, deception, rankling hatred, low aims, indecision,’ he says of the old imperfect society which has to be destroyed, and, thinking of the dishonest decade which World War II brought to an end, we have to agree with him. We are prepared, with certain qualifications, to accept too his denunciation of filiality and paternity. Huxley’s Brave New World presented a society in which family had been abolished as responsible for all our complexes and repressions and, indeed, manias (Our Ford speaking as Our Freud) and, without benefit of official ectogenesis, the Aerodrome proposes to free men from the slavery of wives and mothers. A brave new world indeed, in which sex is a toy and the breeding of children an abomination.

But the brilliant irony of the book lies in its theme of the inescapability of family ties. There is high comedy in Roy’s gradual discovery of who his father and mother really are, the revelation that all the major characters of the story are shamefully, even criminally, related. The unnamed Flight Lieutenant kills his own father, also Roy’s — the Air Vice-Marshal himself. This comic Oedipism is completed by rumours of incest. The death of the father means an end of the Aerodrome, though we cannot be quite sure that it will not rise again. After all, an Air Vice-Marshal presupposes an Air Marshal, and him we never meet. But Roy voices the philosophy which ensures that neither he nor ourselves will ever be tempted again to put on the uniform of the Collectivist State: the imperfect life of the village, despite the Sophoclean dangers that lurk there, is, by reason of its formlessness, its lack of a cut-and-dried philosophy, exciting and adventurous; the Aerodrome, despite its firmness of purpose and its superhuman technology (pilotless planes, for instance), is a negation of life.

This is a symbolic novel rather than merely an allegorical one. I mean that it functions, in spite of the author’s disclaimer, as a realistic work with larger overtones. The scene at the agricultural show indicates what I mean. The Flight Lieutenant, the paradoxical badge of whose complexity as a character is an air force slang which both sounds and does not sound authentic, unleashes a prize bull which stands for the coming totalitarian brutality as well as the primal forces that resist it. He kills, through an accident which is also a deliberate act, the rector whom Roy has believed to be his father: cynically filling his place as air force padre (a rector is a mere ruler; a padre is a true father), he is enabled to find, through a negative road, the truth and the light. The drunken old grocer puts on an act which makes a grotesquerie of the mother-son nexus: ‘Oh mother, I see you in your poor little cottage, poking the fire, thinking, ah, thinking of your wandering son. I thank God you cannot see him. Among the burning globes, in the din and degradation, mother, of a gin hell he is to be beheld. A gaol-bird, mother, a broken reed: and the woman at his side is not his wedded wife.’ The comedy of the book, a quality altogether missing in Orwell’s dystopia, is not to be discounted. But it is a comedy of high seriousness.

The value of The Aerodrome as literature becomes increasingly apparent at each rereading. I mean that one finds new involutions, new paradoxes and complexities at the same time as the solidity of character and of place strikes with renewed force. But the mystery of the work does not dissolve. ‘The national flag’ and the ‘capital’ remind us that we are in a location that is universal, not just English. And yet the language breathes England — not just the flowers and the grass but also the common-sense pragmatism and decency which will defeat, we think, any encroachment of totalitarian aerodromes.

Photography of Pima Air and Space Museum (Tucson, Arizona) by Graham Foster.