Quest for Fire

- Quest for Fire

- About Quest for Fire

- Quest in pictures

- Quest on video

- Anthony Burgess: Talking Animal

- Quest in the news

- Quest for Language

- Quest in Audio

- Quest for trivia

About Quest for Fire:

The 1981 film Quest for Fire is an innovative prehistoric fantasy adventure, and it celebrates its fortieth anniversary this year.

Set eighty thousand years ago at the dawn of time, a primitive tribe, the Ulam, guards its most precious possession: fire. The tribe knows how to tend their fire and how to use it, but they do not know how to make it. When a marauding neighbouring tribe steals their flame, three warriors set out to recapture it in a desperate struggle for survival. But where did the film come from and how was it made?

This article explores the background to Quest for Fire and considers its legacy.

Quest for Fire was inspired by the novel La Guerre Du Feu by J.H. Rosny, published in France in 1911. Rosny was the pseudonym of two Belgian brothers, and the author was the elder of the two, Joseph Henri Honoré Boex.

‘Rosny’ wrote several romances with prehistoric settings, and their vision of primitive man owed something to Enlightenment ideas of the ‘noble savage’, with an idealized and sentimental conception of the goodness inherent in all humanity before it has been corrupted by debased modern civilisation. These ideas were somewhat outdated even in 1911, but the book was hugely popular and sold 20 million copies.

Jean-Jacques Annaud (pictured), the director of the film, read La Guerre du Feu as a child and its reverence for primitive man profoundly affected him. In a 1981 interview he recalled:

Jean-Jacques Annaud (pictured), the director of the film, read La Guerre du Feu as a child and its reverence for primitive man profoundly affected him. In a 1981 interview he recalled:

It entered my subconscious deeply and led me by strange and subtle steps to a point where I just had to make this film or feel totally unfulfilled. I do not mean that I believed every word of it, even as a child. It was the stuff of myth. […] It had an essential respect for those early insignificant creatures, and there was none of the hairy-caveman stuff about it. And of course its central theme was immensely exciting, man’s discovery of the means of making and controlling fire, which anthropologists now agree was a giant step for mankind.

Fire itself is a critical component of the story, of course, but Annaud recognised its symbolic function: ‘its mastery represented a great thrust forward but essentially it is the quest that matters. It is the quest that matters today because we are all still involved in it.’

In 1981 Annaud was thirty-five and one of the most acclaimed film directors in France. After a series of successful commercials, his first feature film, a critique of French colonialism Black and White in Color (Noirs et Blancs en couleur or La Victoire en chantant, 1976) won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and his second, the comedy Coup de tête (Hothead, 1979) did well at the box office. His new status enabled him to pursue his enthusiasm for the subject of Quest for Fire, and he was able to bring the screenwriter Gerard Brach into the project, whose script credits included the Roman Polanski films Cul de sac (1966) and Tess (1979).

Annaud’s aim was ‘to show early man as I believe he truly was, a peaceable creature except when roused, a stranger in an environment he could not understand and had reason to fear, living in a world more profoundly silent and lonely than anything we can imagine today’.

Annaud had little to base this theory on, but was clear that his film was a work of imagination rather than a documentary: ‘Nobody thinks it improper to fantasise about the future, so surely we are entitled to use the same technique when looking back across the millennia into the far, far distant past. Prehistory is as much an unknown landscape as outer-galactic space, beyond purely academic reach.’ Annaud’s film is as such perhaps best understood as a work of speculative fiction, and was later marketed as a ‘science fantasy’.

The imagined silence of early man was reflected in Gerard Brach’s first script for the film, which had extremely limited dialogue and relied mainly on physical directions for the actors. It is here that Anthony Burgess — and the anthropologist Desmond Morris, author of a hugely popular study of the human species, The Naked Ape (1967) — enter the story of Quest for Fire. Annaud realised that he needed a way of dramatizing the growth and development of his early humans as their quest unfolded, and one of the ways in which he did this was to consider the ways in which primitive people might have attempted to communicate through both language and gesture. Burgess was approached to devise new languages for the film that went beyond a monosyllabic ‘mess of grunts and snarls’, as Burgess puts it, to render the complexity and subtlety of the attempts by the tribes to interact.

Annaud remembers Burgess’s linguistic skills as the primary reason the production approached him: ‘I went to Anthony Burgess because before being this famous icon of literature he started as a teacher of languages. For example, he was a teacher in Malaysia where he had to learn Chinese in order to teach English to the Malays. His real speciality was ancient Icelandic, for which he had to learn Danish, all the Scandinavian languages, Norwegian. He also knew how to speak Laplandish. He knew about 25 languages and he was just phenomenal to work with, such a character.’

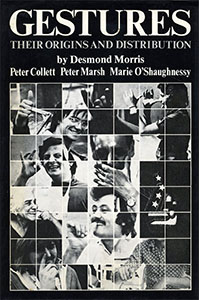

Desmond Morris devised gestures to go alongside Burgess’s language. Reviewing Morris’s book Gestures: Their Origins and Distribution for the Observer in 1979, Burgess describes the importance of physical actions in communication:

Desmond Morris devised gestures to go alongside Burgess’s language. Reviewing Morris’s book Gestures: Their Origins and Distribution for the Observer in 1979, Burgess describes the importance of physical actions in communication:

I despair of ever being able to set any of it down [in words]: the instantaneous flick of a shoulder or the bunching up of a mouth requires too much description. […] Words, some say, are a kind of upstart successor to visual gesture — invisible but audible signs of the night, to be replaced at dawn by the more satisfying semantemes of the eye.

In Burgess’s ‘dictionary’ that he created for Quest for Fire he presents the intended manner of his language in similar terms. Burgess prefaces his lexicon with the direction: ‘all the words must be said with difficulty, awkwardness and very slowly. The sounds come from the chest, and the bottom of the throat. To speak is an acrobatic effort […] They use speech when they have no other means of communication, such as in the dark and in the distance’.

The production made considerable demands on the actors. The remote locations used for the production were suitably wild and uncivilised, and included the Scottish mountains, northern Canada, Lake Magadi in Kenya, and Iceland. After training sessions in the language and gestures to be used in the film, including a workshop with Burgess and Morris, the actors spent several months partially clothed and in both freezing and very hot conditions, living in tents and a long way from home.

Everett McGill, who played the lead character Naoh, described the filming experience: ‘It has changed me. I came back some days from those utterly desolate locations, days when we were without even the most rudimentary comforts we all normally take for granted, exhausted but uplifted. I have had to endure in the most basic sense, to show the strength of a lion, the cunning of a hunting dog, the persistence of a cat to get through them.’

His co-star Ron Perlman, making his feature film debut, had a similarly challenging time: [During the training sessions] I found myself making chimp sounds, knuckle-walking, barking, trying to acquire the feel for animal movement, eye contact, instinct. Afterwards came the actual filming and I can’t imagine anything harder, the long hours, the lack of shelter from the heat and cold. I had been a heavy-smoking, night-loving New Yorker but I proved something to myself.’

McGill and Perlman both suffered minor frostbite but made full recoveries. Also starring was Rae Dawn Chong, who went even further: ‘The horror was real. It was hellacious — the most trying, almost soul-killing experience making that film. There was zero clothing, a language we couldn’t understand, treacherous conditions, and for what?’.

Annaud seems to have been as much concerned with the animals in the film as with his actors. ‘We had been training elephants to behave like mammoths for six months. Those elephants were on contract to be back at their circuses in September. We had to shoot soon, but couldn’t. Due to strict laws around transporting four-legged animals in and out of Iceland, we couldn’t get them into the country on time. Then, a volcano erupted near where the ranch we had built for them was located. And the delays saved the elephants, because if they had been there, they would have perished.’ The scene was eventually completed, with the Ulam tribe mingling with the herd of mammoth-like elephants, a considerable hazard for the actors especially as the scene ends with a stampede.

Despite these challenges, the film was a success both commercially and critically. It received $55m at the box office, against a budget of $12.5m, and while reviewers were initially uncertain at how seriously to take the adventures of the primitive peoples, the sincerity and conviction of the performances led to more comparisons being made to films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) than less cerebral fare such as One Million Years B.C. (1966). Quest for Fire won five Genie Awards in Canada, including Best Actress for Chong and the Cesar in France for Best Picture, as well as an Oscar and a BAFTA for Best Makeup, and Best Foreign Film at the Golden Globes. Annaud said later that he was approached about possible sequels, including Quest for Water and Quest for Iron, but turned them down. His next film was The Name of the Rose (1986), an adaptation of Umberto Eco’s novel. Anthony Burgess had in fact reviewed this novel positively in 1983 and was approached by Eco to write the screenplay for the film, but his involvement ultimately came to nothing.

Burgess’s languages for Quest for Fire can be set alongside the other invented languages in his oeuvre: the Castitan language in his novel MF (1971), the language based on Indo-European for the ritualistic chants in his translation of Oedipus the King (1972), and an unpublished invented language based on a fusion of English and Hebrew, originally intended for Man of Nazareth (1979). In the 1999 television documentary The Burgess Variations there is footage of Burgess coaching the actors in the correct pronunciation of his language: as Annaud remarks in the film, ‘he liked repeating the words to relish them, he had this pleasure in language. I remember him, with this large voice, saying ‘ATRA! ATRA! [the Ulam word for fire] Yes, this is good! […] The movie was quite a success, and they interviewed people after the movie and said: “Who is the director, do you think?” Everybody came up with “Anthony Burgess”. I was very flattered.’